- Home

- Annie Zaidi

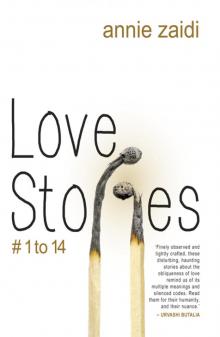

Love Story #1 to 14

Love Story #1 to 14 Read online

LOVE STORIES # 1 TO 14

ANNIE ZAIDI

HarperCollins Publishers India

New Delhi

For my Grandma, Safdari (alias Shehnaz), and Grandpa, Jawad, who loved me in separate ways, but always gently and without question

CONTENTS

LOVE STORY # 10

(aka The one that was announced)

LOVE STORY # 1

(aka The one that ended)

LOVE STORY # 3

(aka The one that was fulfilled)

LOVE STORY # 4

(aka The one that badly wanted)

LOVE STORY # 12

(aka The one that tumbled out of the balcony)

LOVE STORY # 5

(aka The one that went up in smoke)

LOVE STORY # 9

(aka The one that climbed out of a bucket)

LOVE STORY # 13

(aka The one that was washed up by the tide)

LOVE STORY # 8

(aka The one from Radheshyam (B) Cooperative Housing Society)

LOVE STORY # 11

(aka The one with enough insurance)

LOVE STORY # 7

(aka The one with cheese in it)

LOVE STORY # 2

(aka The one that came limping back)

LOVE STORY # 6

(aka The one that was foolish)

LOVE STORY # 14

(aka The one that stepped off a broken-down bus)

Acknowledgements

LOVE STORY # 10

(aka The one that was announced)

She was fifty-seven, going on fifty-eight, and the thought that she would be retired soon filled her with despair.

It was her last year at work and she knew she would be offered a bye-bye package soon, no extensions please. She wasn’t going to beg, of course. If they had asked her to stay on another year, even six months . . . but they had probably found a replacement already. She was sure of that. But they were sure to give her good references. Perhaps, at another office. It wasn’t impossible. There were all sorts of new companies and they needed someone. Taking calls, making calls, writing invoices, filing. Younger people didn’t know all this. She wouldn’t work for the salary, of course. But even a little something.

She had enough put by. There wasn’t a money problem. Nor was she worried about what to do with herself. It would be nice, really, to have nowhere to go, nothing to do. Since the age of thirty-five, there was nothing she had longed for more.

Read a tabloid over a long, leisurely breakfast, then the Today before lunch, then maybe dig up a new recipe for the evening. She longed to drift about the house in a nightie, catching glimpses of her rumpled self in the mirror. She wanted to potter from kitchen to balcony to bathroom to sofa set. Watch TV. Oh yes, she would like that very much.

She would like it even better after her neighbours went off to work, or college, or school, or wherever they had to go. Then she could play loud music through the day. It was her greatest joy on Sunday afternoons, but she wasn’t allowed to. There were slanging matches with the neighbours, and if she refused to turn down the volume, then those people would respond to her playing of sixties’ hits, like ‘Yahoooo!’, by putting on cricket commentaries at maximum volume. Not even music. Just cricket talk!

When she was at home and they were away, then she could listen to her music. And she would never worry about being late for work. There were few things worse in this city than her incessant, belittling commute. Sticking to a desk for nine hours, dealing with people who ignored her or shouted at her, being curt with strangers who wanted to speak to the bosses right away. No appointment, just like that. Glaring at her, as if she stopped them for the joy of it. Who would miss all those aggrieved, accusing faces?

She would have enjoyed the idea of retirement if it wasn’t for him. How was she going to meet him if she didn’t get out of the house and go to work?

This was a serious problem. She had been trying to wrap her head around it for nearly eleven years now. Surely, there must be a solution. Surely, people didn’t let go of people they loved just because they didn’t go to office any longer.

She did have the option of keeping up her commute. She could still take the 9.10, because that’s where he was most often, although he could also be on the 8.22. Still, as retirement day drew close, a terrible thought had begun to haunt her: what if he too was due to retire? How, then, would they maintain contact?

Until now, she had never considered the possibility of his retirement. She hadn’t thought that he too would have grown to a certain age, a certain build, with a certain kind of lined, baggy face. That he too waited for the day when he could stop working.

She had spent twelve years wallowing in the luxury of making him whatever age she wanted him to be. The idea of his retirement seemed incredible. For the first two years, she remained fixated on thirty-five. She had decided that he was younger. He sounded like it, the way he fumbled with announcements; his hesitation before announcing timing or platform number, his obvious haste in getting away from the microphone.

She had pictured him from the moment she first heard his voice. There was a softness around its edges. Maybe it was because he had been asked to speak at short notice, but his voice sounded high-pitched, breathless.

Perhaps he could hear his own voice when he spoke. That must have made him even more awkward, for he halted at all the wrong points, stressed the wrong syllables so that the cadence of the announcement was distorted. Some passengers in the ladies coach had begun to giggle. They all guessed that the man was not used to making announcements. Usually, it was a mellow, confident woman’s voice that shimmied along their morning commutes, barely disturbing those who fell asleep.

There was something wrong that day – a signal wasn’t working, or somebody had fallen down on the tracks again, who knows? It happened all the time. Everyone would fret, restless fingers, twitching knees, clicking tongues. Once, a train had been stalled for three hours, and nobody knew why. A bunch of passengers had hopped off, onto the tracks, and begun yelling. The train driver was beaten up. Some of them were arrested later. It was all very frightening, but afterwards, the railways started making regular announcements. There was a loudspeaker system in each compartment. If something went wrong, they would announce it, and tell you how long it would take to fix it.

Of course, it usually took longer. But still, it was reassuring to hear a human voice say what was going on. A live, hesitant voice that suggested that you were going to be okay. Things got fixed. You didn’t stay stuck forever. You would get to wherever you wanted to go. She liked the announcements. Each time the train was late, she would make a note of the voice – how it sounded, the exact words used, who the announcer might be. She would retell it in office. Women her own age would gather to listen; they understood. They would even say something about the voices in their own trains. Little stories built up around the announcements.

But more and more of those women had retired, or quit. More and more, she felt foolish, trying to tell younger women about train announcements and voices. She never talked about his voice, of course. Not even to her older friends. That one was too special to be shared.

She couldn’t explain why he was so special. Maybe the way he had read out the delayed schedule that first time, foolishly racing through the whole announcement, then repeating it in three languages – Marathi, Hindi, English. His English was heavily accented with Marathi, and on days when he was going to announce a cancellation, his voice sometimes cracked with sheer nervousness: ‘Passengers, kindly pay attention . . . passengers . . .’

She could picture a young man, not yet confident in his own skin. Someone who wore grey pants and mixed-cotton shirts, blues and whites, to work. His eyes might b

e large, and if he wore glasses, they would look even larger. He probably blinked when he got nervous. And he probably had to write down the announcement in his own handwriting before he approached the microphone. That was what he sounded like, and her heart went out to the nervous young man.

Over the years, she got better at picking up voices. She began to pay close attention. There were usually three women announcers on her route, and one man who sounded older, more gruff. Then there was him, his voice utterly unsuited to the making of public announcements. Did they make him announce things just to hear him sound foolish? Did they laugh at him?

She could imagine that. Colleagues were like school children, so innocently cruel. That was why she never spoke about him to her own colleagues. One would tell the other, and then there was no stopping them. Meanwhile, the announcements grew more frequent. Somebody would announce the name of the upcoming station, then the name of the next station. This was when she developed an instinct. The announcement system would bristle, crackle, the microphone would be switched off, and on again, and exactly two seconds before the voice began to speak, she would venture a guess – would it be him, or not?

Nine times out of ten, she was right.

It delighted her. It made her flush. This ability to pick him out, pluck him out of the radio silence. She whispered a name she didn’t even know, and thought: ‘There you are. I knew it was you.’

It was like the game she had played as a child. Someone would sneak up behind you and put their palms on your eyes. Then you had to guess who it was. Sometimes, you used tricks – rings, wristbands, scars, nail-length would lend clues. Or smell, or even body temperature. Still, you mostly counted on your instinct. She remembered the thrill of being right, and also her longing to be known, to be guessed at. When she put her hands over a chosen friend’s eyes and the friend somehow guessed correctly, she would feel fulfilled, redeemed, whole. If a friend guessed you right again and again, it meant there was a special bond.

And here she was, getting it right almost every time. It meant something, didn’t it? Thrilled, she resolved to take the 8.22 every day. That was the train on which she heard his voice most often.

The 8.22 wasn’t a good train to catch. Ideally, she would have taken the 8.16, which stopped at her stop. The 8.22 went further, was more crowded, and it left her with less time to look for a shared cab that would take her to office. But those were minor adjustments. You had to make adjustments, didn’t you? Everyone makes some small sacrifices for people with whom they share a special bond.

It made her heart race, just to think it: she, making sacrifices. For someone she loved. It made her set aside the tabloid’s daily crossword and grab her own pulse. Her pulse raced so fast, she grew pale, and for a minute, she thought she might be having a stroke. She was far out into her forties, and these days, you heard of even younger people having strokes. Brain. Heart.

She breathed deep, and told herself to calm down. She accepted a bottle of water from a concerned college student who sat across the aisle. And when she stood up and moved to the train door, she was careful to move slowly. Just in case. But she neither collapsed nor felt sick. In fact, when she heard his voice again, announcing her stop, she felt light as a sparrow. Full of flight and song.

After that day, the commute seemed like very little effort. She got up earlier, took the train the opposite way, and waited until the train emptied out. Then it became her 8.22 morning special. She could stretch out her legs in the near-empty compartment for a few minutes. She would shut her eyes; anticipation lingered on her skin like a fine sweat.

Of course, she was too old to make room for stupid fantasies. She did not imagine that his voice was hers alone, that he was making announcement after announcement – time, platform, station name – only for her benefit. She also knew that he didn’t know yet. About their special bond. But that was alright. That didn’t matter.

A few years ago, her youngest sister had finally gotten married and moved out. Her own house seemed to be expanding now, like it was taking a deep breath, stretching its arms. She sighed with relief as she did away with the vestiges of her sister’s sour presence. She got rid of pictures of saints and gurus, and fake hibiscus flowers, and old boxes of chocolate that some suitor had bought at some happy moment. When everything was swept out and put in the garbage, she felt as if she was breathing again.

She was alone, and free, and – whether anyone knew it or not – she was in love.

Late at night, with only the ancient ceiling fan and its infernal racket for company, she often wondered what his name was, what he looked like. It wouldn’t be that difficult to find out. She knew a girl who worked in the railways and took the train with her on Saturdays. They had struck up a conversation once, and still nodded pleasantly if they spotted each other. She could always find out how these things worked – who made announcements for which train, where the office was, how shifts were managed.

She could take leave from work. She could go to the railways’ office. Maybe she could discreetly peer into the room and see which mouth was leaning forward to speak into the microphone for the 8.22. She would recognize the voice, of course. And then perhaps he would lean back in his chair, and perhaps he would stand up and call out to the peon, or perhaps he would turn around to go looking for a cup of tea. Then she would see his face.

She played the scene over and over in her head. He might have a moustache. Not a big one. Just a neat, slender moustache to liven his face, one that brought colour and symmetry to a square jaw.

Next Saturday, she spotted her railways’ friend. She pushed through the crowds to stand next to the girl. They made conversation in the usual way: long time, parents, babies, chikoos, hair clips. Then the next station approached, and as the announcement was being made, she suddenly blurted out: ‘Who does it? I mean, do you do this, the announcement?’

The railways’ girl laughed. ‘Me? I just work at the ticket counter.’

And that was all. She could not find the words with which to press on, to go on asking questions about announcers and their duties and locations. Besides, she persuaded herself that it wouldn’t be so lovely if she knew. If she knew his name, where he lived, how he looked, it would deepen her temptation to go and talk to him, to demand an acknowledgment in return for her feelings.

She wanted him to welcome her presence, to think about her with the same ferocity that made her get up early, catch difficult trains, just to hear his voice. She wanted him to scan platforms, hoping to catch a glimpse of her figure as she hurried past. She wanted him to want her, wait for her, pretend to have just bumped into her the way friends keep bumping into each other on the railways. It was working out fine as long as she did not expect anything. Once she had tracked him down, she would start expecting. It was inevitable. How could she help it? So it was best not to know the details.

It might turn out that he was married. Maybe he had children. He must be at least thirty-seven or thirty-eight, judging from his voice. If she discovered that he was a married man, it would ruin things. She would have no peace. No, she chose not to find out.

And yet, the tug of that voice grew strong. It throbbed in her blood with such insistence that it demanded a body. She simply had to attach a face to it, so that she could think of a proper man.

So she decided to find a face to match the voice. Initially, she found a new one every day. In the morning, when her head was muddy with to-do lists, the never-settling churn in her stomach blocked out all thought. But when the day’s work was done, she would start to unwind. She would pick up a sandwich from outside the office building. Where other people ran to get cabs, she strolled out at a leisurely pace, taking a longish walk along the seafront, then on to the station. She would wait for a slow train, and while she waited, she would peer keenly into the faces of passing men.

She picked on men who fit her idea of what he must look like: around forty, dressed like the average male government employee of the clerical order – cheap c

otton-blend pants, striped shirts, half-sleeved, a steel watch.

It was funny, how many possibilities there are. One might think this was a certain type – a type that melted into itself so that the individual stood shrouded in anonymity on a crowded railway platform. But, no. The harder she looked at them, the more distinctions she found.

There were men who wore only grey shirts, and men who wore neat beards and stroked their own faces constantly. She rather liked them, and for several months, she decided that her love was one such man. She would keep an eye out for men with neat beards and a small, neat paunch. She particularly liked the type who did not tuck their shirts into their pants. It was part sloppiness, part vanity – shirt ends hanging loose over belts to hide a small belly – and she found it endearing. There was one man in particular. He took the same train and he seemed to be in no hurry to get anywhere. He would often miss a train if he was busy drinking a glass of carrot juice at the stall, or simply because he was too engrossed in his evening newspaper to bother with the hustle of boarding.

She would watch this man from the window of the ladies’ coach. He wouldn’t step into the train until the last possible moment. It meant that he wouldn’t get a place to sit, but he didn’t seem to mind. Maybe he didn’t have a family to rush back to. Maybe he had been sitting at a desk all day and needed to stand upright. Maybe he liked the breeze in his face and chose to stand near the open doors, as the more foolish college students did.

But after four months, she suddenly couldn’t spot him any longer. Maybe he changed his route. A new house? Or a new job?

In any case, the disappearance of that leisurely gent didn’t bother her very much. Her love was the owner of the voice, and the voice was still there. She just had to find him another face.

There was a man with a slim moustache, in his mid-thirties, who ran a snack stall at the station. He was tall and slim, although one would imagine that being surrounded by so many samosas and vada-pavs and laddoos and hard pastries, a man would run to fat. But he stayed slender.

Love Story #1 to 14

Love Story #1 to 14